BLOG: Interdisciplinarity is key for studying energy transition

Main content

In order to anticipate, inform and guide transitions to low-carbon energy we need to understand why and how such transitions happen. But energy transitions involve changes in energy markets, technologies and policies. How can we disentangle the drivers, preconditions and impacts from these three interlinked systems? The difficulty is that each of these systems is the domain of a separate discipline and these disciplines cannot speak to each other easily because they use different concepts, theories, and methods. Energy markets are primarily studied by energy economics, energy technologies by sociology of technology and science-technology studies (STS) and energy policies by political science.

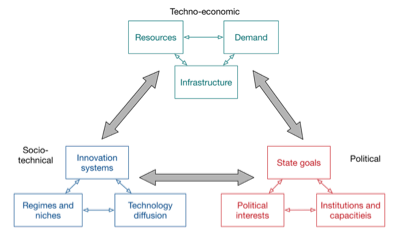

In a new paper we propose a common language for these disciplines to communicate about energy transitions. This language is inspired by Elinor Ostrom's (a Nobel Prize laureate in economics) work on bringing together economists, sociologists and political scientists to study governance of socio-ecological systems such as fisheries. The proposed framework for analysing national energy transitions is structured along the three fields of knowledge, which we call the 'three perspectives on energy transitions': techno-economic with its roots in energy economics and energy systems analysis, socio-technical, with its roots in sociology of technology and Science, Technology and Society (STS) studies, and political, with its roots in political science. For each perspective, we define 'top-level variables', as shown in the figure below. We explain how to analyse national energy transitions through expanding these variables into more detailed second- and third-level variables and constructing explanatory models of transitions.

This framework builds on the strengths of each discipline. Take energy economics and energy systems analysis, which are at the foundation of global climate-energy models used by Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) and other organizations providing authoritative policy recommendations. These models are very good in describing how energy production and use in various sectors and regions should transform in order to avoid dangerous climate change while providing sufficient energy for growing economies. However, they cannot evaluate whether, under what socio-political conditions, and in which countries such transformations are feasible.

Political science on the other hand, focuses on explaining why a particular policy was introduced in a particular country in light of this country's national interests, political and institutional landscape, however it sometimes neglects material factors which provide context for policy formulation and implementation as mere 'contingencies'. As a result, political scientists often make a mistake of ascribing certain changes in energy systems (e.g. the growth in renewable energy or phase-out of coal) to declared political goals (e.g. climate mitigation) rather than to more down-to-earth factors (e.g. reduction in technological costs or resource depletion). Finally, socio-technical studies explore how new technologies emerge and spread in societies, however their emphasis on innovation and lack of attention to how societies are transformed by 'mainstream' trends (such as demand growth due to increased population and prosperity) and goals can leave gaps.

We illustrate this framework by a comparative analysis of electricity transitions in Germany and Japan (elaborated in another paper). In the early 1990s, Germany and Japan had similar electricity systems dominated by coal and nuclear power, however in the next 20 years Germany has become the world leader in solar and wind energy while firmly deciding to phase out nuclear while Japan dramatically expanded its nuclear fleet while deploying only small amount of new renewables. We show that some aspects of this difference are explained by techno-economic, some - by socio-technical, and some - by political factors.

The challenge of analyzing energy transitions from different disciplinary perspectives illustrates the existential need for CET. It is only through bringing together scholars from different disciplinary backgrounds that we can produce scholarship which is not only robust in explaining energy transitions but also actionable and relevant for society.