- Data collection on microplastics may aid protection of both human and environmental health

– Given that the health impacts of microplastics remain a relatively new and evolving field, there is a pressing need for robust scientific evidence to draw meaningful conclusions, says Damaris Benny Daniel. Her SEAS project, a collaboration with obstetricians at Haukeland University Hospital, will involve an extensive clinical study on the effects of microplastics during pregnancy.

Hovedinnhold

Through the SEAS project, I have had the opportunity to collaborate with obstetricians at Haukeland University Hospital, and we are now planning a more extensive clinical study focused on the effects of MPs during pregnancy.

What attracted you to becoming a researcher, and then to the SEAS programme?

One of the key findings of my doctoral research was the detection of microplastics (MPs) in edible tissues of 14 out of 21 seafood species examined from the Southwest Coast of India. The public outreach of the research outcome was frequently met with some prominent questions such as, “so what if we are consuming MP-contaminated seafood, will it not be ejected from our body? Is there any scientific evidence of a major risk?”. These questions have piqued my curiosity and have motivated me to dive deeper into the potential health risks of MPs, especially through food. The SEAS programme and the thematic area offered by the Department of Clinical Medicine turned out to be the perfect fit—it provided the ideal environment and support to continue exploring these questions in depth.

Foto/ill.:

Damaris B. Daniel

|

Foto/ill.:

Damaris B. Daniel

|

Can you give a general description of your SEAS project?

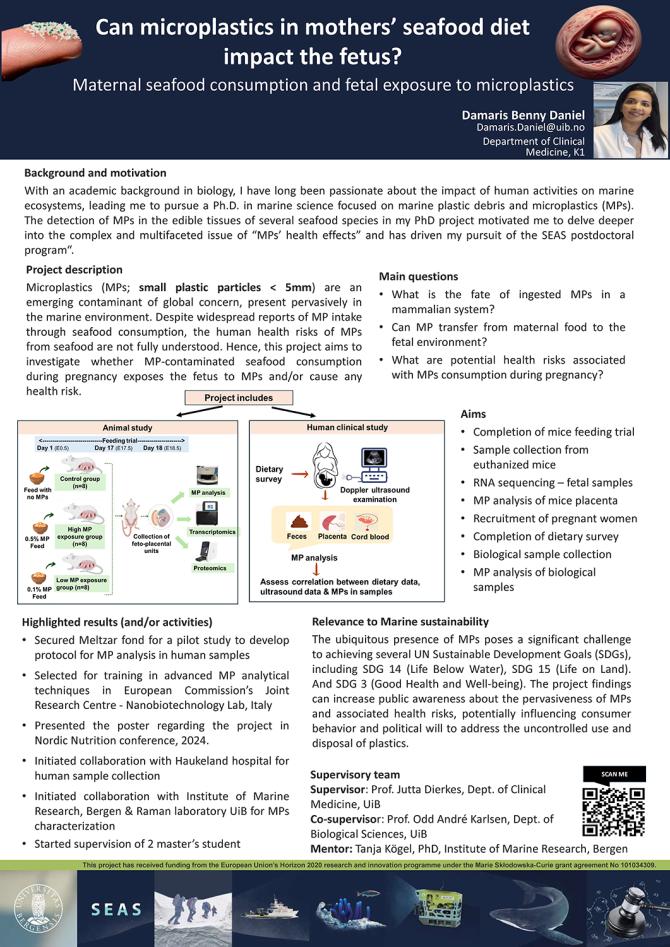

Microplastics—tiny plastic particles less than 5 mm in size—are now widespread in the environment and across the world’s oceans. While it’s known that they enter the food chain, including seafood, the potential health risks to humans remain poorly understood. My SEAS project investigates whether consuming microplastic-contaminated seafood during pregnancy could impact fetal health. To explore this, we are conducting a two-part study: (i) Animal experiments using pregnant mice, where we feed pregnant mice with MP spiked feed and assess potential health effects through transcriptomic analysis. (ii) A clinical study examining the relationship between maternal seafood consumption and the presence of MPs in maternal stool, as well as in cord blood and/or the placenta. Our findings aim to generate data that can support efforts to protect both human and environmental health in the face of rising plastic pollution.

Are you starting to see results that could guide your future research?

While the analysis is still ongoing, we’ve already found MPs in the fecal samples of 80% of the pregnant women who took part in our study. That’s a strong indicator of widespread exposure and tells us this is something we need to look into further.

The primary aim of my SEAS project is to generate pilot data and conduct a feasibility study that can serve as the groundwork for a larger, more comprehensive investigation. Given that the health impacts of MPs remain a relatively new and evolving field, there is a pressing need for robust scientific evidence to draw meaningful conclusions. Through the SEAS project, I have had the opportunity to collaborate with obstetricians at Haukeland University Hospital, and we are now planning a more extensive clinical study focused on the effects of MPs during pregnancy. Additionally, the project has enabled me to gain certification and experience in animal studies, and the preliminary data generated will support the integration of an animal research component into future projects.

Have you had any fieldwork during the SEAS programme? What was that like?

Not in the traditional sense—medical research doesn’t often involve fieldwork in the way environmental studies do. But running a clinical study was a completely new kind of experience for me. Talking to participants, conducting surveys, and hearing their thoughts about plastic exposure gave me a fresh perspective. It’s been a unique and enriching part of the research process.

What have been the pros and cons of the SEAS programme in terms of resources, community, and collaboration?

Both microplastics and medical research are resource-intensive fields, and since this project sat at the intersection of the two, it was challenging to manage resources and carry out everything we envisioned. That said, the SEAS program offered significantly more funding than a typical postdoctoral project, which was very helpful in supporting our work.

One of the biggest positives has been the supportive community—everything from writing retreats to informal meetups with other fellows at a similar career stage have greatly enriched my postdoc journey. My SEAS supervisor, colleagues in the department and the SEAS administrative staff have all been incredibly supportive. Honestly, the pros have far outweighed the cons. I’m genuinely grateful to be part of this programme.

This experience has shown me how powerful it is to bring in tools and ideas from different fields to solve difficult problems. It’s definitely something I plan to carry into my future research—creating collaborations that span disciplines.

Foto/ill.:

Damaris B. Daniel

|

Foto/ill.:

Damaris B. Daniel

|

Foto/ill.:

Damaris B. Daniel

|

Foto/ill.:

Damaris B. Daniel

|

What has your experience of living in Bergen been like?

Bergen is beautiful. The landscapes are stunning, the city has a calm, friendly vibe and helpful people. The weather is moderate compared to what I expected, and the public transport works really well. Overall, it’s been a great place to live and work.

How has the interdisciplinary aspect of the SEAS programme contributed to your project?

Microplastic pollution is a complex issue—it touches everything from environmental sustainability to food safety and human health. The interdisciplinary focus of SEAS allowed me to move from a marine science background into biomedical research. This experience has shown me how powerful it is to bring in tools and ideas from different fields to solve difficult problems. It’s definitely something I plan to carry into my future research—creating collaborations that span disciplines.

How does your project connect to the UN Sustainability Goals or marine sustainability more broadly?

My work directly supports UN Sustainability Goal 14.1, which aims to reduce marine pollution by 2025. By helping us understand the potential human health effects of MPs, the research also feeds into SDG 3 (Good Health and Well-being) and SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production). The findings will not only fill gaps in scientific knowledge but also help shape better communication strategies and interventions to reduce plastic pollution and its impacts.

How do you spend your free time? I enjoy reading nonfiction and listening to podcasts that expand my perspective and support my personal growth. I also love traveling, as it allows me to experience different cultures, cuisines, and ways of life. Moreover, I try to staying connected with family and friends, mostly through digital means as many live far away, and I meet them in person whenever possible.

Where do you see yourself in 5 to 10 years? I see myself leading research projects in the field of toxicology, hopefully at a university or research center in Europe. I’d like to continue working on complex environmental issues that affect public health and that need interdisciplinary solutions.