20.08.2007 - BIO gets its own Whale-Fall!

The Mesocosm Laboratory at Espeland Marine Biological Station has been a centre for much fascinating research. Christoffer Schander is a professor at the Department of Biology at the University of Bergen and a group leader in the Centre for GEOBIOLOGY. He explains that now it will be possible for researchers working at the Laboratory to have access to a new, unique, natural laboratory; a whale-fall.

Hovedinnhold

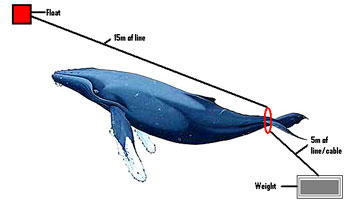

The opportunity developed when a whale stranded just outside Bergen in mid-June. The rotting carcass made headlines as neighbours and boaters in the area complained. However, Andrew Sweetma and Craig Smith at the University of Hawaii suggested that the carcass could have great scientific value. Thanks to a great deal of goodwill from the local authorities, it was towed and submerged at about 600m deep in Korsfjord, an area accessible to the Biological Station,.

Whale-falls have been attracting the attention of the marine research community as it is being recognised that over time they have an associated chemosynthetic microbiological fauna that is similar to that found around hydrothermal vents and cold seeps. In the final stages of decomposition, which may last for years, whale-falls are often surrounded by a thick mat of chemoautotrophic bacteria. The bacteria in turn, provide energy and nutrition for larger organisms.

Around 20 microbial species have already been described from whale-fall microbial communities. The presence of a whale carcass provides researchers with a unique opportunity to study how deep-sea organisms respond to the sudden arrival of a significant amount of organic material.

Natural and artificial whale-falls have been studied off the coast of California where Craig Smith (see image to right) and his colleagues have submerged carcasses to depths of 2000m. In 2003 researchers in Sweden submerged the carcass of a young whale near Tjärnölaboratoriet off the western coast of Sweden. The Korsfjord carcass is the first time a whale-fall will be able to be scientifically supervised in Norwegian waters through all its phases of decomposition.

Researchers have found that the decomposition of a whale carcass takes place in three distinct phases. The first phase, the mobile-scavenger stage, is dominated by the presence of scavengers such as crabs, sharks, shrimp and millions of amphipods that remove most of the soft tissue in a matter of a few months. The second phase, the enrichment opportunist stag, is dominated by opportunists. Large aggregations of bristle worms and shrimp-like cumaceans consume any scraps that remain. The third phase lasts years and is the sulphophilic phase, which is dominated by organisms that live on the sulphides produced by the whale carcass. This phase has the greatest biological diversity with many different organisms from many different groups.

Future studies at the Korsfjord whale-fall natural laboratory will be related to the work at the newly established Centre of Excellence at UiB, the Centre for GEOBIOLOGY. Schandler explains that he expects that there will be some fascinating results from this carcass in the years to come. He expressed his gratitude to Craig Smith and Andrew Sweetma at the University of Hawaii for their input and collaboration that has enabled researchers at UiB to initiate this unique research opportunity, which will be of great value to a number of ongoing international research initiatives at the university. (more information)