A widely used RNA assay labels the wrong molecules in several model organisms

After a routine experiment raised suspicions, Steinmetz group researchers joined forces with collaborators to highlight the limitations of a commonly used RNA labeling product.

Hovedinnhold

DNA and RNA are both biological compounds found inside living cells. They are made from similar molecules but serve very different functions – DNA permanently stores genetic information, while RNA copies this information and uses it as needed for various cellular functions, such as producing proteins.

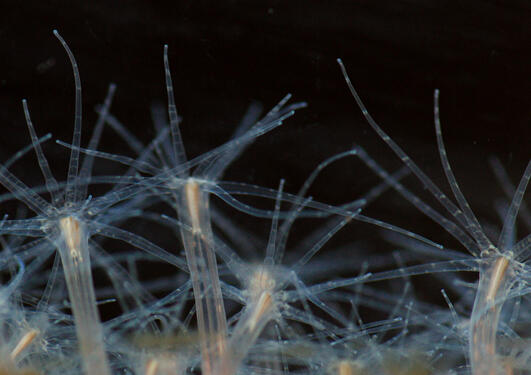

For her undergraduate project in the Steinmetz group at the Michael Sars Centre, Malin Kjosavik planned to visualise RNA production in the sea anemone Nematostella vectensis using a common technique based on the incorporation of 5-ethynyl uridine (EU) into RNA. “As we analyzed the data, the labeling patterns we observed looked very similar to what we had previously seen from DNA labeling”, Kjosavik explained. “It turns out that the simple, but very surprising explanation was that EU incorporated into DNA rather than RNA in Nematostella.”

In the light of these new findings, the team revisited the literature and found several reports in other systems where EU labeling closely resembled previously reported DNA patterns. Could this issue affect other organisms? To find out, Kjosavik and researcher Kathrin Garschall designed a protocol to investigate EU incorporation across models, and recruited collaborators from the Universities of Bergen and Vienna to test their hypothesis. The results of the study, recently published in BMC Molecular and Cell Biology, show that Nematostella is not the only exception to the rule.

"Our findings suggest that there could be major differences in nucleotide metabolism between species" - Malin Kjosavik

Colleagues were able to confirm that EU works as a specific RNA label in a human cell line, and in specific cells in fruit flies and in the comb jelly Mnemiopsis leidyi. However, experiments in the sea anemone Exaiptasia diaphana and in the marine worm Platynereis dumerilii showed clear evidence of EU incorporation into DNA. “Our findings suggest that there could be major differences in nucleotide metabolism between species”, Kjosavik said. “It also illustrates a broader principle in biology: experimental tools and labeling strategies do not always behave the same across systems.”

The team hopes that their work will help researchers interpret their results and encourage them to validate techniques in their own model system. The expected positive impact on the molecular biology community is even more remarkable given the junior status of the lead author. “It was a pleasure to supervise Malin, who already as a bachelor's student boldly and methodically challenged the status quo”, Garschall commented. “Her exceptional experimental ‘detective work’ will hopefully spare researchers working on RNA in less established model systems countless hours of second‑guessing their EU results.”

As a takeaway message, Kjosavik addresses fellow researchers: “When your RNA results are highly unexpected and exciting, that’s usually the moment to get suspicious and check whether it’s just DNA in disguise!”