The Thesen Company

Norwegian entrepreneurs in South Africa: Networks and entrepreneurship in the period 1870 – 1950.

Main content

Erlend Eidsvik

erlend.eidsvik@global.uib.no

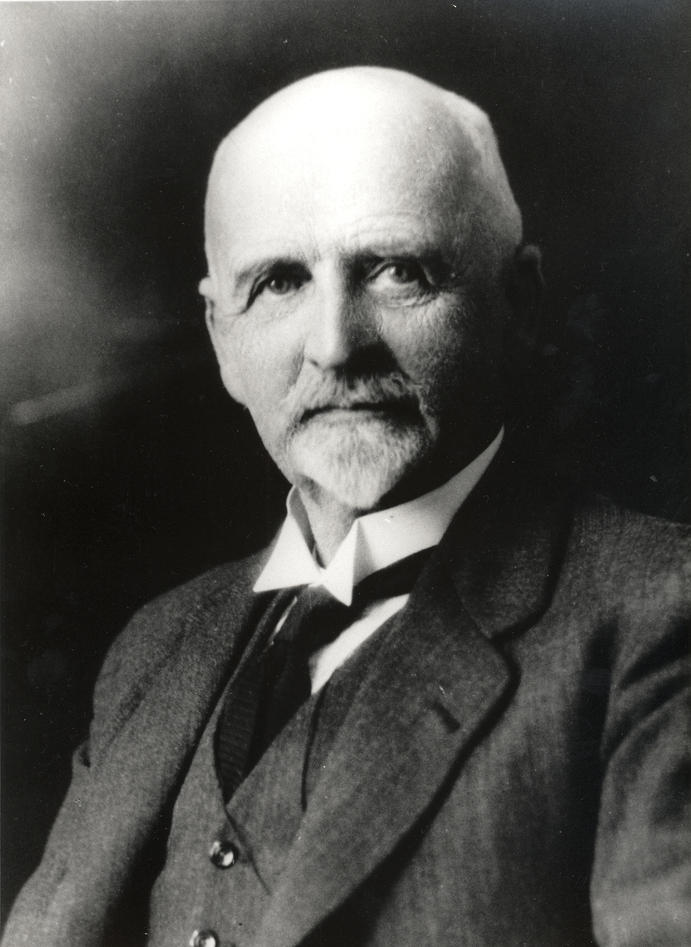

Arnt Leonard Thesen established his hardware enterprise in Stavanger in 1840. Few years later, Thesen went into shipping that soon proved to be a profitable business. Thesen became a wealthy and respected man in Stavanger, and he was also for several years a member of the Stavanger Municipal Council. Stavanger had grown into a prosperous trading port in particular due to the repeal of the English Navigation Act in 1849. However, the Danish-German war from 1864-67 triggered a recession in trade and shipping, and in 1868 the economic slump forced several companies in Stavanger into collapse, among them A.L. Thesen & Co (Winquist 1978).

Thesen could not see any future in Stavanger, and decided to migrate to settle a new life for his wife and his nine children. The British Vice-Consul in Stavanger issued a letter allowing the Thesens to settle in a British colony. One of the remaining ships, the schooner Albatros, was loaded with timber for sale upon arrival. In July 1869 the Albatros departed Stavanger with 13 members of the Thesen family and seven others. The expedition planned to sail for New Zeeland.

Two and a half months later the Albatros reached Cape Town, and after a week’s stay for repair and to load provisions, the ship and its crew continued on its way to New Zeeland. Stormy weather at the Cape of Good Hope forced the ship to return to Table Bay and Cape Town for repairs. At this point, the Thesens made contact with the Swedish-Norwegian consul, Carl Gustaf Åkerberg. The consul, also a merchant, shared his concern about the shortage of ships for transport along the South African coast.

The geo-political scene (or more correctly, the Euro-political scene; the Austro-Prussian war and the impending Franco-Prussian war) caused a shipping shortage noticed as far away as South Africa (ibid.). Åkerberg intermediated contact for the Thesens with merchants in the Cape Province to ship cargoes along the coast. The original plan sailing to New Zeeland was first postponed and later set aside, as the economic prospects in coastal trade in South Africa seemed advantageous.

A few months and several costal cargo voyages after their arrival, the Thesen family settled in Knysna, a small fjord-like port in the Eastern Cape. Starting with timber shipping, the Thesens advanced into saw-mills and subsequently forested land properties within few years. When Arnt Leonard Thesen died in 1875, the company leadership was handed over to one of the sons, Charles Wilhelm Thesen.

The Thesen Company expanded and in the following years new ships were added to the fleet, more land was acquired and new economic activities implemented, i.e. oyster farming, hardware stores, supermarkets, whaling ventures, gold mining, railway construction and truck transportation. Charles Wilhelm Thesen also involved himself into local politics, and became a member of the first municipal council of Knysna, and even became mayor of the town in the periods 1890-93 and 1921-24. From a moderate start by shipping timber along the coast, the Thesens & Co grew into one of the leading companies in South Africa in just a few decades, and is still a major enterprise in South Africa.

The research project

Considering this brief historical sketch, the thematic departure point for the proposed project is to illuminate Norwegian economic activities in South Africa in the period 1870 to 1950, analysing the establishment and entrepreneurship of Thesens & Co as a case. First of all, how is it possible for a bankrupt timber trader from Stavanger to establish what should become a multi-million Rand enterprise in South Africa?

This parent question triggers a set of research questions that will be scrutinized. When investigating the establishment of the Thesen & Co in South Africa, who can be identified as the contacts in South Africa, and how was the network established and maintained? Further on, is it possible to depict a Scandinavian, or even a Norwegian network in South Africa in this era, that both communicated within South Africa and even on a global scale, or at least bilateral scale to Scandinavia and Norway? And – at an even more specific level, who were the key persons affiliated in such networks, both in Norway and in South Africa?

Norwegian networks in South Africa

A few Norwegians (26, to be precise, according to Danish records) – mainly sailors and employees of the Dutch, Swedish or Danish East India Company – had settled in the Cape Province even before the British seized The Cape Colony from the Dutch in 1806. However, the group was small and when the first Norwegian missionaries arrived in early 1840; they could not find any Norwegian milieu, networks and persons to contact apart from the Swedish-Norwegian consulate in Cape Town (Jørgensen 1991).

When the Thesens arrived 30 years later, emigration to South Africa was still very limited. However, from 1885 onwards, the amount of Norwegian and Nordic migrants increased. Kuparinen (1991) reveals an interesting contrast when comparing South African and overall migration patterns from the Nordic countries: the mean age was much higher due to low proportion of family migration, and the immigrants were recruited from urban areas and were well educated. These conditions might be decisive for development and establishment of a Nordic and Norwegian business network in South Africa.

Even though the Thesen adapted rapidly to South Africa, it seems that a network and contact to Norway was maintained throughout the period. Knowledge in Norway and the Nordic countries about South Africa was limited in late 19th century, as only a few books and reports about South Africa were available in Nordic languages (Kuparinen 1991).

However, from 1886 onwards, upon the establishment of the gold mining industry, emigration to South Africa from the Nordic countries increased remarkably. From 1887 to 1904 a total of 892 Norwegian vessels – particularly departing from the southern coast of Norway – were docking in South Africa (ibid.). These figures indicate a comprehensive contact between business partners in Norway and South Africa.

As the Norwegian population in South Africa increased, the Norwegian Society (“Den Norske Forening”) was established in Durban in 1896. From 1914 to the early 1950’s the Norwegian Society published the magazine “Fram,” containing articles about Norway and Norwegians in South Africa. The magazine was mainly written in Norwegian language (Winquist 1978, p108). “Fram” is thus literally an evidence of the network of Norwegians that existed in South Africa, particularly after the turn of the 20th century.

Shipping business requires ships, and Thesen & Co also used Norwegian contractors for purchase of new vessels. As late as 1915, Thesen & Co ordered for “Porsgrund Mekaniske Værksted” to build the freight ship “Outeniqua”. Whaling ships for the Union Whaling Co. (which also was a Norwegian initiated enterprise in South Africa) were also built in Porsgrund in 1924 and 1927. Even though these business connections are known from historical records, scholarly attention on the characteristics and dynamics of these networks has been marginal.

According to Winquist (1978), the Swedish-Norwegian Vice Consul was evidently a catalyst for the Thesen business dynasty. But knowledge concerning the role of networks and thus the dynamics and expansion of the company are relative scarce. Hence, is it possible to identify a Norwegian or Nordic network in South Africa that was beneficial for the development of the Thesen & Co?

Entrepreneurship

The establishments of networks described above is one of the main characteristic for the entrepreneur, and the framed research questions will be analysed applying theories and discourse on entrepreneurship. Starting with Schumpeters (1942) classical theory, entrepreneurship calls for a specific type of personality and conduct, which differs from the economic man.

The entrepreneur takes advantage of rationally based components of his or her environment, to achieve and create for own sake, and to establish family dynasty. Belshaw (1955) refined the theory, identifying four main stakes in entrepreneurship, that is: a) the management of a business unit, b) profit taking, c) business innovation and d) uncertainty bearing. Particular analyses concerning the two last points, innovation and uncertainty bearing, will be stressed in the analysis of Thesen & Co.

Barth is less instrumentalistic in his analysis on entrepreneurship. He emphasises the entrepreneur as aspect of role: It relates to actions and activities; not rights and duties. Furthermore, it characterizes a certain quality or orientation in the activities (Barth 1963). Barth advocates a wider research agenda, taking into account the social context of the community, and emphasise that the entrepreneurial activities and the features of social life of the community must be made commensurable through being treated in a common frame of reference (ibid, p 6).

Contemporary investigations of entrepreneurship further develop Barth’s ideas, and calls for an integrated approach, exemplified by Aldrich and Waldinger (1990) and Martinelli (1994, 2004). Their essays focus on diverse variables as structure of markets, access to ownership, state policies, group characteristics, predisposing factors, and resource mobilization. Martinelli (2004) further advertise for a multidisciplinary comparative approach in research on entrepreneurship, capable of integrating the analysis of the context (market, social structure, culture) with a theory of the actor (both individual and collective) including motives, values, attitudes, cognitive processes, and perceived interests. Applying an integrated approach advocated by Martinelli could mould for an improved understanding and knowledge about the Thesen & Co in particular and entrepreneurship in the colonial period in general.

Time and space perspectives of the development of the Thesen & Co

Applying diffusion and innovation theory to the establishment and growth of the Thesen & Co adds a complementary dimension to the project. From a geographic perspective, diffusion involves the propagation of a phenomenon in a manner such that it spreads from place to place (Brown 1999). Most commonly the phenomenon is an innovation – a new product, new idea, new technology, new organizational structure, – where ‘new’ means new to a particular place by way of adoption. Hägerstrand’s (1967) works on innovation diffusion constitutes one of the pillars in diffusion theory. Hägerstrand observed what he called a spatial order in the adaptions of innovations.

In this context, innovation and diffusion of ideas and products need to be analysed according to scale, from global to local levels. On a global level, emphasis will be set on how innovative ideas are lifted out of a local contexts and re-constructed independent of space and time. This perspective is tangent to Giddens view on modernity, where space and place is independent of each other (Giddens 1994). The rather rigid model Hägerstrand presents will be modified by applying the perspectives of disembedding conceptualised by Giddens (ibid.), and thus lift the discussion into a discourse of time, space and modernity.

Accordingly, the proposed project will search to explore the nature and process of diffusion of new ideas, technology and products in the context of the Thesen & Co. It will be necessary to analyse the global diffusion process, that is, diffusions of ideas and innovations from Europe to South Africa and vis-à-vis. But it is also necessary to analyse the process of diffusion on a local level; how new ideas and innovations are spread through networks in a local South African context.

Bibliography

Aldrich, H E and Waldinger, R, 1990. Ethnicity and entrepreneurship. In Annual Review of Sociology 16, pp. 111–135. California: Annual Reviews.

Barth, Fredrik, 1963: The role of the entrepreneur in social change in northern Norway. Bergen/Oslo: Norwegian University Press.

Belshaw, C., 1955: “The Cultural Milieu of the Entrepreneur: a Critical Essay”. Explorations in Entrepreneurial History, vol. VII No. 3. Cambridge Mass.: Harvard University Press

Brown, L.A., 1999: “Change, continuity, and the pursuit of geographic understanding: Presidential address”. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 89:1-25. Washington: Association of American Geographers

Giddens, A., 1994: Modernitetens konsekvenser. København: Hans Reitzels Forlag.

Hägerstrand, T., 1967: Innovation Diffusion as a Spatial Process. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Heradstveit, D and Bjørgo, T., 1992: Politisk kommunikasjon. Oslo: Tano.

Jørgensen, Torstein, 1991: “Norwegian Emigration to South Africa in the 19th Century.” In Norse heritage, Vol II. Yearbook. Stavanger: Det Norske Utvandrersenteret.

Kuparinen, Eero, 1991: An African Alternative: Nordic Migration to South Africa, 1815 – 1914. Helsinki: Finnish Historical Society

Martinelli, A, 1994. Entrepreneurship and management. In: Smelser, N J and Swedberg, R, Editors, 1994. The Handbook of Economic Sociology. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Martinelli, A, 2004: International Encyclopaedia of the Social & Behavioural Sciences, Pages 4545-4552. London: Elsevier

Schumpeter, J.,1942: Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy. New York: Harper and Row.

Winquist, Alan H., 1978: Scandinavians and South Africa. Their impact on the cultural, social and economic development of pre-1902 South Africa. Cape Town/Rotterdam: A.A.Balkema