At the Frontiers of Change, Despite a Continued Burden of Morality

In February Thera Mjaaland defended her thesis on Tigrayan women and girls’ contributions to processes of change in a context where gendered norms in relation to female modesty and morality continue to go largely unquestioned.

Main content

Thera Mjaaland’s thesis is entitled At the frontiers of change? Women and girls’ pursuit of education in north-western Tigray, Ethiopia. The social anthropologist’s connection to the region of Tigray in North-Ethiopia dates back to 1993, when she first came there as a freelance photographer.

On Tuesday 4th of June at 14:00 Mjaaland will give a lecture at the Resource Centre on the use of photography in her research. Click here for more information.

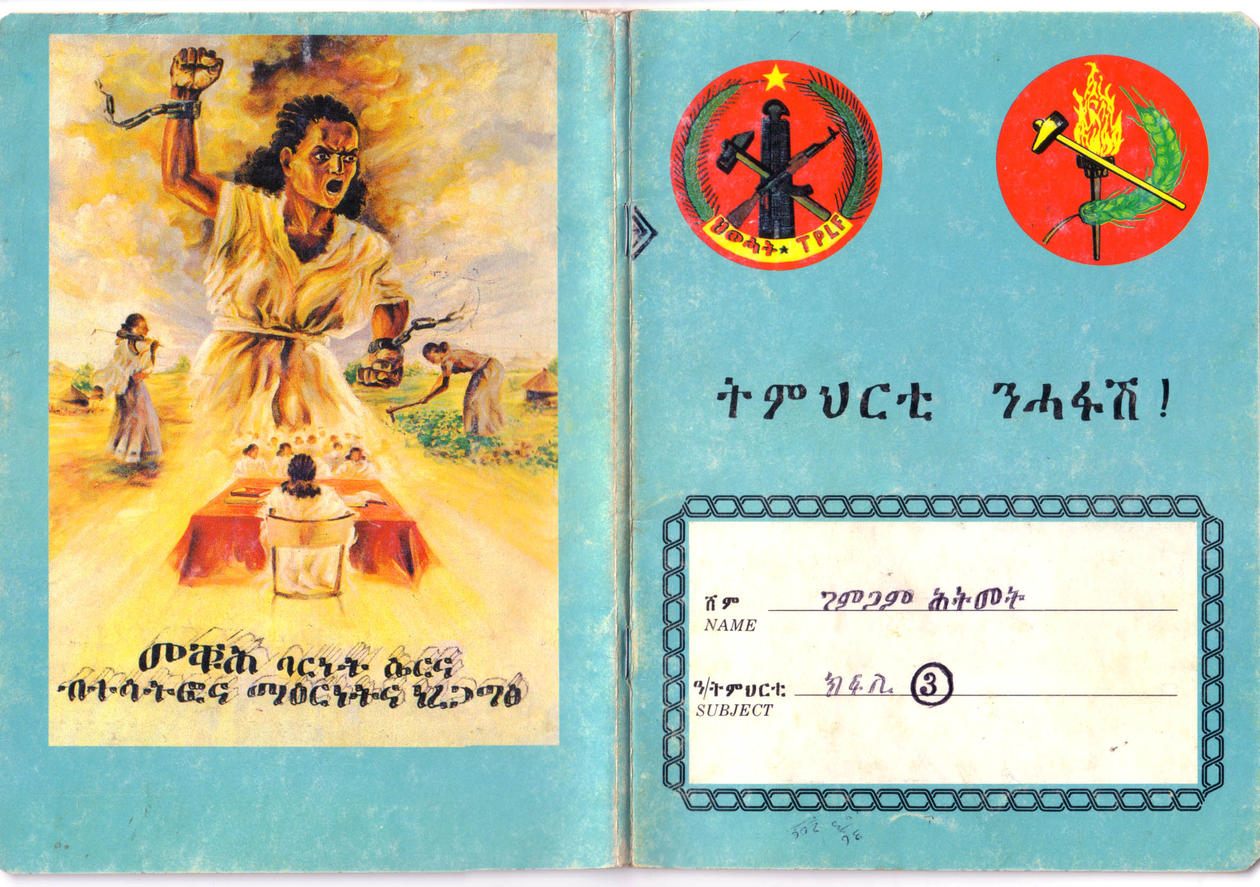

The civil war between the military Derg regime and the insurgency led by the Tigrayan People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) had ended just two years earlier, with President Mengistu Haile Mariam fleeing to Zimbabwe as the TPLF-based Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF) seized power in Ethiopia.

Giving a more nuanced account of Ethiopia

The eyes of the world were no longer on Ethiopia as the civil war came to an end, but Mjaaland wanted to follow post-war processes in the region where the insurgency had emerged. This interest brought her to the study of anthropology.

– Initially, my area of interest was Tigray and Eritrea, where women had participated in the liberation armies of both TPLF and EPLF (Eritrean People’s Liberation Front). However, when the war between Eritrea and Ethiopia erupted in 1998 I fell down on Tigray, where I had a more extensive social network. As a photographer I was interested in the selective images of catastrophes circulating in Western media from Ethiopia, and from Africa more generally. We see fewer peacetime images, which in a news-context, would be less sensational. Consequently, images from the famine in 1984-85 might still inform Western understandings of Ethiopia, Mjaaland asserts, in spite of the significant changes taking place in the country today.

Gender norms difficult to change

There are relatively few foreign anthropologists who have taken interest in Tigray. However, Mjaaland insists that this northernmost region of Ethiopia represents an interesting case of contemporary processes comprising both change and continuity:

– There are significant changes in the region today in terms of infrastructural development, as well as in the area of health and education. Gender norms seem to be more difficult to change though. Even with legislation and policies in place which include women’s rights and gender equality, this might not necessarily be reflected in the reality on the ground. Even though girls are in a majority in elementary school in the region, a trend now also continuing into the lower level of secondary school, the burden of morality follows Tigrayan female students in their pursuit of education. If they are more active and outspoken, more mobile than the female modesty ideal requires, they are easily classified as immoral. Like in the case of the Tigrayan fighter women who took up arms during the struggle, female forthrightness can still result in women and girls being classified as ‘men’ or ‘boys’. These gendered dynamics are not encompassed in the new policies, says Mjaaland.

Education as a bargaining card

At the base of female morality is the ideal of virginity, leading parents to marry their daughters while still underage:

– Some of the elder women I interviewed had been married at 8-10 years of age. Despite the legal marriage age in Ethiopia being 18 for both girls and boys today, rural parents often marry their daughters at around the age of 15-16, which, no doubt, shows that change is taking place. However, the case is also that the law is seldom, if ever, enforced in my area of study. A rural community leader who had married his daughter when she was around 16 said: “We have demolished that law ourselves”. Girls are considered sexually mature from the age of 15-16. She risks being classified as ‘damaged’ if her parents do not secure their daughter’s respectability through a culturally sanctioned framing of her sexuality by way of marriage, before she finds a boyfriend on her own. Since rural students have to move to urban areas to continue school after eighth grade, the virginity ideal has repercussions for these female rural students’ education in ways that boys do not encounter. In this way the burden of morality continues to follow girls into education, says Mjaaland.

– On the other hand, girls use education as a bargaining card in their negotiations with parents. The case is also that not all rural girls are forced into marriage, adds Mjaaland, who stresses that there are also rural parents who support their daughter’s further education when having to move to urban areas outside their control.

Some of the girls who are married underage are also allowed to continue school after marriage, but as Mjaaland emphasises, this would also depend on their husbands. Some girls even manage to divorce their husbands soon after being married to pursue their education. Hence, educational success depends, to a large extent, on the girls’ own assertiveness and commitment to education. It is in this respect that these Tigrayan girls place themselves at the frontiers of change.

Mjaaland’s first fieldwork trip to Tigray as a social anthropologist was in 2002, as a master’s student, permitting her to apply what Signe Howell and Aud Talle has classified as a ‘multitemporal’ perspective on the situation of women in her doctoral study.

– Back then I met seven girls from the same village. They had moved to an urban area to continue their education after fifth grade, and lived two or three together in small rented quarters. Of these seven, three ended up in university. One of these three was in fact married while still in school, but continued her education to a university degree while giving birth to two children along the way. In this context pursuing an education does not necessarily follow a linear and uninterrupted progress, but adapts more pragmatically to the unforeseen unfolding of life.

Change through practice, not words

In her dissertation Mjaaland proposes that girls’ increased school attendance, as altered practice, has a bearing on processes of change, even in the absence of a critical discourse, which is how change is understood from feminist and critical theory perspectives with a neo-Marxist base. The question is to what extent a critical discourse that accommodates these changes is allowed to emerge from altered practice.

– This is a larger theoretical question which I’ll probably ponder on the rest of my life. It is also the case that, historically, open criticism in the Ethiopian context has been difficult. This has resulted in socio-cultural dynamics based on a common layering of communication, which means that much is said implicitly. This gives people a scope of action even when norms or political circumstances restrain their options. To under-communicate what is done in practice creates spaces for agency that circumvents these restraints. This is also a strategy women utilise to avoid social sanctions when venturing beyond the gender norms, Mjaaland says, but which, at the same time, restrains the possibility for alternative discourses to emerge.

– If I had come to Tigray as a stranger during my PhD period I wouldn’t have gotten far. It has taken time to understand this layered communication, and there are things that people waited for years to tell me. For example, it took one woman I know nine years before she told me she had been with the fighters during the struggle, Mjaaland notes.

Struggling for equal rights

Women played an integral part in the Tigrayan struggle against the military Derg regime, which was backed by the Soviet Union. By integrating women in TPLF as fighters, the liberation front was not only able to increase its numbers but also gained legitimacy.

– Civil women also participated actively during the struggle. They were involved in clandestine work, acting as couriers, hiding injured soldiers and bringing food, because their normative gender role made them less conspicuous. Participating one way or the other, women were also involved in their own revolution within the revolution for equal rights.

But women’s participation was also seen as an affront to gender norms:

– When TPLF started to teach women how to plough, it challenged the divinely ordained roles of men and women, as seen by the Ethiopian Orthodox Church. Tigrayan priests are also reported to have murmured that the big famine in 1984-85 was caused by this transgression, which in their view had incurred the wrath of God. In spite of women ploughing having become an icon of women’s equality, the resistance soon put an end to this teaching program, Mjaaland notes, since TPLF risked losing the support of the church, and with it the support of a highly religious population. One question I have posed is if women were betrayed by the very liberation movement they supported when it came to normative issue of gender roles.

– Many of the fighter women who were able to utilise the educational possibilities during the struggle, and managed to continue afterwards, have fared well and occupy positions in politics and administration today. Those, who did not follow the educational track, often found themselves reverting to traditional work tasks for women after the struggle. It is also the case that while the TPLF-based regime change in 1991 has secured gender equality in legislation and gender-sensitive policies, current politics are centred on development and poverty eradication. This priority, which was accepted by the Tigrayan fighter women in position during the struggle, is based on the premise that poverty had to be eradicated before gender justice could be fully accomplished.

– Women’s Association of Tigray, which started as part of the liberation movement but became an independent NGO in 1997, has also slid from being a political organisation to becoming more of a development organisation. While having provided important inputs to Ethiopian legislation through their advocacy work, the current focus is on women’s empowerment by way of providing microfinance loans to women together with short trainings, rather than activism, says Mjaaland.

Using photography as research method

As part of her PhD project Mjaaland made use of her expertise as a photographer. Often people would ask Mjaaland to take pictures, deciding themselves how to pose when photographed. What emerged in this series of photographs taken over several years are rural girls posing while holding their schoolbooks, which can be viewed at the top of this article:

– When asking me to photograph them, these rural girls often presented themselves as students. Based on several pictures and repeated photographing the girls’ poses in these images visualise how rural female students try to negotiate normative gender identity in between new possibilities opened up by education and the gender norms of an agrarian society. Being photographed has itself enabled a space where these young girls attempt to mediate the situation they are in as female students.

– These photographs can also be interpreted as an ideal image of what these girls want to become, as they create a link to an imagined future as educated women. This interpretation is also based on a whole array of contextual knowledge and the fact that in the present situation in rural Tigray, with scarcity of land for the younger generation in addition to ecological degradation, both girls and boys are in search of alternative futures to the harsh lives their parents have lived.

Thera Mjaaland's thesis can downloaded from BORA – Bergen Open Research Archive: https://bora.uib.no/handle/1956/6361

For more of Thera Mjaaland’s work in photography and anthropology, visit her website http://thera.no