COMMON ENDS: Particular themes to be adressed

Main content

Definitions of cultural heritage

Although cultural heritage is in common usage both among grassroots and governing bodies, it is a concept in gradual change and with conflicts and paradoxes built into it. One definition holds cultural heritage as essentially those things, ideas and practices that define the people in question historically and culturally. It is in essence what defines a social group, and its expressions as inalienable, sacred, mythological, secularly or religiously central and crucial for the reproduction of its values. But it can also be argued that heritage should instead be defined as a process of regulation by the state or other institutions. Cultural heritage then becomes a unit of management, with authoritative expert discourses separating it out from lived life. The two definitions contradict each other, since one is about the free-flowing, intangible and changing ideas some people might have of themselves, in terms of memories, communal bonds, values; what it means to be a person and a human being. The other definition implies hegemony, control and authority. These contradictions of definitions fuel the tensions and conflicts that we will investigate in COMMON ENDS. The split in perspective becomes especially demarcated in for instance repatriation cases, or in encounters between the public and scientific experts in matters of heritage protection. Our approach seeks a way out of these dichotomies and conflicts, and interconnects with the rise of public anthropology, public archaeology and citizen science where there has been a call to merge internal and external perspectives on heritage.

Orders of governance

The network will highlight overarching changes in governance of cultural heritage, and what this can tell us about the conflicting organization of society; the state of cultural heritage as sites of public interest and access, the relation between the public and the private, and the redefinitions of culture and history implied in governmental practices. We explore the concrete manifestation and effects of change in governance practice; going from the national to the regional, from the scientific to the public, detailing the consequences of over-national involvement, or going from public management to private, or from a national level to the level of ethnic groups.

Grassroots engagements

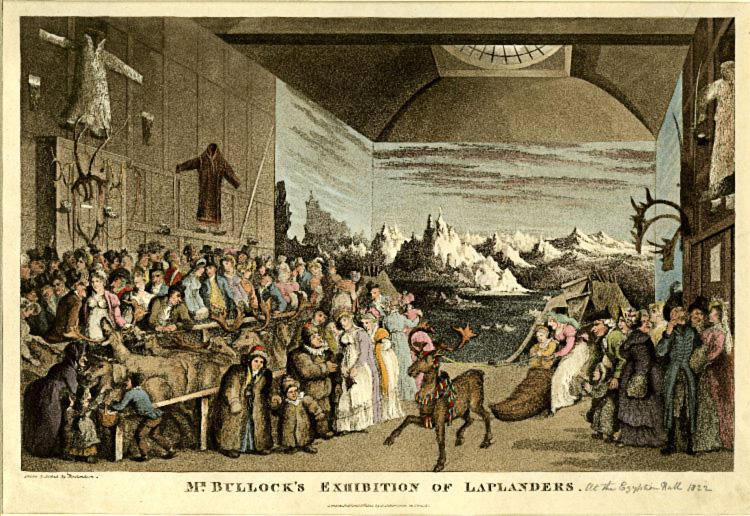

The network will highlight the ways in which cultural heritage is of importance to how people define their identity as a people, their religious life, their history and belonging and their reproduction from the present and into the future. We investigate the value of cultural heritage as a specifically enchanted form of wealth, as it is having reproductive functions through rituals, pilgrimage or more secular ceremonies such as national celebrations. We are here dealing with practices that often run counter to the processes featured in governance – notably involving things and practices that resist universal and scientific definition, and that feature as sacred, magical and intensely meaningful with a local value that inhibits alienation along market logics. We will here be looking at the various pressures that such sacred or inalienable objects or sites face when becoming subject to the governing domain of cultural heritage.

Whose heritage?

Before the 1972 World Heritage Convention prefixed the adjective ‘cultural’ to heritage, its meaning – in English and most other languages that we are aware of – was understood literally, as the intergenerational inheritance transfer of assets or estate, usually within a family configuration. The prefix ‘cultural’ added other claimants to the mix besides the immediate heir(s), such as the nation-state and other political authorities and cultural experts, because the meaning and value exceeded that of the immediate inheritance. Usually the prefix of ‘cultural’ comes with a whole bundle of problems concerning whose cultural heritage it is. The potential of generating economic benefit from tourism and gentrification; the effect of secularizing religious spaces, the wholesale dispossession colonized and indigenous people, the limitation of access to protected buildings or artwork deemed national heritage – This is just a short list of possibilities that have been documented in the literature where the question comes up: Whose heritage is it really?