Reinventing the laws of the sea

In partnership with Palau's UN Mission and IOC-UNESCO, the University of Bergen arranged a side event at Our Ocean to discuss the science necessary to secure marine biodiversity beyond national jurisdiction as part of international law.

Main content

In the side event The role of research and capacity-building in the United Nations BBNJ negotiations, during the 2019 Our Ocean conference in Oslo, co-hosted by the University of Bergen, the Permanent Mission of Palau to the UN and the Intergovernmental Oceanographic Committee (IOC-UNESCO), the science-policy nexus on the marine Biodiversity Beyond National Jurisdiction (BBNJ) negotiations at the UN were put to the test.

For the University of Bergen, this has been a burning issue for some time with scientists from the university being directly involved in the BBNJ process, first and foremost Professor Edvard Hviding from the Department of Social Anthropology. He has been assisting Palau as scientific adviser in the negotiations. He was also the moderator for this special side event, which was the only side event at Our Ocean to directly address BBNJ.

BBNJ 101

“This is like a BBNJ 101,” said Ambassador Ngedikes Olai Uludong, Palau’s Permanent Representative to the United Nations, who has a key role at the BBNJ negotiations as Facilitator of the IGC’s working group on capacity building and transfer of marine technology, in the opening speech at the side event before proceeding to define her four key areas in the BBNJ negotiations:

- capacity-building and the transfer of marine technology

- marine genetic resources

- environmental impact assessments

- marine protected areas

“These are the four areas in which we are trying to progress and advancing on this will decide how the treaty will become,” said Uludong, “the key to making the treaty work, which is missing a lot in the negotiations, is the science. This is one of the issues I have been concerned with as a facilitator of the BBNJ process. It is important to bring in organisations such as the IOC and other scientific partners to ensure the ocean science in the process.”

She urged everyone to go home to their governments to encourage making science key in the BBNJ process.

“It is a considerable task to bring the science interface into this process,” said Uludong, who also was critical of how prepared her own Pacific region of the world really is.

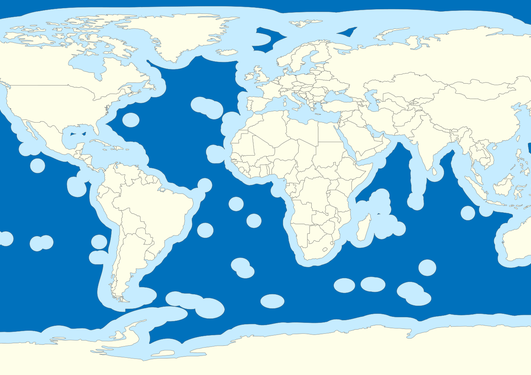

“The world's biggest high seas are in the Pacific. The biggest exclusive economic zone (EEZ) is Kiribati and the second biggest EEZ is French Polynesia,” she said and pointed to the interesting fact that even if this is French territory, it is the EU who is present in the BBNJ negotiations. This creates challenges the Pacific nations need to be more aware of.

From science to policy

Both the next two speakers represented the science part of the science-policy nexus, bringing in Pacific, Norwegian and global perspectives to aid the ongoing BBNJ negotiations.

First out of the two scientists in the panel was Dr. Yimnang Golbuu, CEO for the Palau International Coral Reef Centre (PICRC), who presented various studies on everything from shellfish to tuna.

“Natural resources don't know borders. Fish and crustaceans are in free float between EEZs and the high seas,” said the coral reef specialist, “they move in and out between zones and our study of DNA in marine organisms documents that biodiversity can show the same information in EEZs and the high seas.”

He mentioned several examples, including one on tuna-coral reef dynamics.

“We look at connectivity at the trophic level between tuna and reef organism in our national waters. Look at isotope signals and see where the food for the tuna is coming from. We can extend this to the high seas,” said Golbuu.

Integrating ocean management

The former Chair of IOC, Professor Peter M. Haugan, who was involved in the creation of the UN Decade of Ocean Science, addressed integrated ocean management processes in his speech.

“Many of the actors connected with processes in the UN to create this legally binding instrument of BBNJ, have asked the IOC: How can we use science and refer to it in this instrument? The dialogue and interest we had through IOC has been really inspiring for me as an ocean scientist,” said Haugan.

He was, however, not only upbeat, and underlined that scientists across disciplines need to ask the necessary questions for research-based knowledge to be put at the heart of BBNJ.

“Who knows what marine genetic resources are? What can they be used for? What is their value? For whom? Should they be shared? Can people just go out there and get these resources? Can we make patents out of this,” asked the oceanographer urging the scientific community to pursue informing policy-makers even more than scientists do at present.

We have the diplomacy

“Biodiversity doesn't know the borders that we have created in a meeting room in New York,” said Kjell Kristian Egge in the closing speech in the side event, echoing Palau's Dr. Golbuu.

Mr. Egge is International Law Adviser of the Law of the Seas at Norway's Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Norway's Head of Delegation to the UN BBNJ negotiations.

“Management should be based on the science that is there,” said Egge stressing that governments need to use the science community to create a research-based BBNJ result.

“The IOC already has a global network. There are institutions that we can draw on, and this agreement should be an overarching something connecting all the dots. That is what we all hope that this agreement will be.”

The importance of capacity-building

He then pointed to the essential work done by Ambassador Uludong.

“The ambassador is facilitating the negotiations on capacity-building. People have realised that we are talking about improving ocean management in a global sense,” said Egge, “to do that we need to make everyone involved in ocean management support the common goals we make. Important that capacity-building is done in the right way to make all relevant actors actually manage the ocean and to contribute to that common management.”

Once again echoing Dr. Golbuu, the international law adviser drew parallels between EEZs and the high seas in relation to the BBNJ negotiations.

“This agreement is for the high seas, but I always try to make the point that through capacity-building, our hope is that that will also improve the national capacity to manage your own national waters,” he said before ending on a cautiously optimistic note, “and also to utilise the resources in a sustainable way. This is an important point that we are in agreement on, but the environmental issues will set the framework for how this will be done.”