A global approach to inequality and pandemics

In response to the Covid-19 pandemic, the research programme GRIP launched a series of interviews on global inequality in March 2020. With more than 20 interviews out, GRIP is now looking at how to bring the debate on inequality into the mainstream.

Main content

The Global Research Programme on Inequality (GRIP) examines inequality around the world, bringing in scientists across academic disciplines. The programme has a particular focus on the 2030 Agenda and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). GRIP launched in 2019 in collaboration between host institution the University of Bergen (UiB) and the International Science Council (ISC). GRIP builds on the Comparative Research Programme on Poverty (CROP, 1992-2019).

GRIP’s Scientific Director is Professor Bjørn Enge Bertelsen, who leads the programme committee. We asked GRIP five questions on the conclusion of the miniseries COVID-19 and global dimensions of inequality, which GRIP’s Research Coordinator Maria Dyveke Styve responded to.

- Congratulations with passing more than 20 interviews in the series (and counting) in a short space of time. Apparently, it has not been hard to find people willing to discuss Covid-19 and inequality?

“It became increasingly clear that the impacts of the virus, and of the lockdown measures in particular, were distributed very unequally, and were also bringing to the fore many of the underlying social, economic and political inequalities that were there before the outbreak. Partly because of this, many researchers had quite a lot to share from early on about the connections between Covid-19 and global inequalities. Drawing on the extensive international network at UiB, through GRIP’s Programme Committee and the network of the International Science Council, it was not hard to find people across the globe willing to discuss these questions from very different angles and contexts.”

- When you look at the goals you set for the series and the interviews so far, what are you most pleased with?

“As the series has progressed, it has been important that the interviews have had a very good geographical spread, and that they have covered a diversity of perspectives and topics ranging from health governance, migration, global economic crisis, the racialization of pandemics, governance and settler colonialism and what kind of societal models we need for a post-pandemic future. The series has also had wide reach, and we were very pleased that our website had over 5800 visits, and that it has been one of the most read series on the International Science Council’s Covid-19 portal.

We are also really happy with how the series has made it possible for us to be in touch with a plethora of brilliant scholars, and with how this paves the way for future collaborations. For example, we are now collaborating closely with Divine Fuh, who is the Director of the Institute for Humanities Africa (HUMA) at the University of Cape Town. He has been a key driver in establishing Corona Times, a blog that has already had a huge success in providing a platform for scholars across the world to share their perspectives on the Covid-19 crisis, and to strengthen the role of the humanities and the social sciences in understanding the pandemic.”

- Have there been any surprises during the making of the series? Particularly notable quotes or discoveries that you can use in future GRIP work?

“Part of what we found particularly engaging was the way in which many of the contributors historicized and contextualized the pandemic, which is incredibly important in the work ahead to understand the implications of the crisis on the multiple dimensions of inequality.

For example, in the interview with Edna Bonhomme at the Max Planck Institute in Berlin, she emphasizes how pandemics do not materialize in isolation, but rather how they are “part and parcel of capitalism and colonization.” Eugene Richardson, who is both a physician and an anthropologist at the Harvard Medical School, makes a similar point when he argues that the pandemic has to be understood within a longer historical context of health inequalities.

Osama Tanous, a paediatrician in Haifa, also traces the long history of settler colonialism and racial capitalism and how this informs the ongoing responses to the pandemic in Israel and Palestine.

Throughout the interview series, many of the contributors emphasize the importance of local, contextualized knowledge and experience when dealing with the crisis. Universal template-like solutions are problematic and often result in heightening inequalities, as for example Anwesha Dutta at CMI argues has been the case with the lockdown in India. Jessica Kampanje-Phiri, at the Lilongwe University of Agriculture and Natural Resources, makes a similar point when she states that instead of looking at the African continent a recipient of global template-type solutions that have been developed elsewhere, there is a need to start thinking of Africa as being part of the solutions which can be replicated elsewhere.

In terms of what kind of post-pandemic futures can be imagined, Divine Fuh at the University of Cape Town (UCT) argues that we need “a system that runs on steroids of care rather than one operating on opium of destruction”.

Rachel Sieder, at CIESAS in Mexico, highlights that while we face a global crisis of unprecedented dimensions, “our opportunity to challenge the global capitalist model is also unprecedented,” pointing to the example of the Zapatista movement in Mexico affirming that another world is possible.

Fe’íloakitau Kaho Tevi, development entrepreneur and diplomat working in the Pacific Islands, describes how collective responses to the pandemic in many of the islands build on a strong sense of communal living and caring for each other, that are key to any post-pandemic futures.

Drawing on our network at the University of Bergen, our series also included an ethicist perspective from Ole Frithjof Norheim at the Department of Global Public Health. Professor Norheim has been involved in the public debate on the need for ethicists in addressing global health challenges, also linking this to greater issues of structural inequalities.”

- How do you plan to move on with the series and how to implement it into GRIP’s upcoming activities?

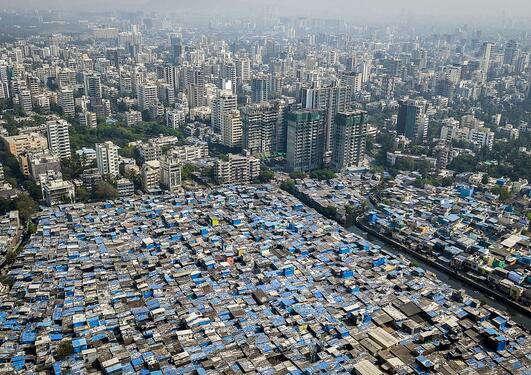

“In fact, we are planning to start up a new series from August, which will focus more on broader questions relating to urban inequalities in the aftermath of the outbreak. Now that the situation in many countries is beginning to normalize, what has this new normal shifted towards? The new series will have the title “Inequalities in the Post-Pandemic City”, and just like the first series, it will contain interviews with scholars from across the globe.”

- This sounds really exciting and we look forward to the launch of your new series. In August and in conjunction with this, GRIP is partaking in the Bergen Exchanges, where the theme encompasses Covid-19 and inequality. How did you get engaged with this event organized by the Bergen-based LawTransform research community? And what are you planning for this?

“We have been invited to co-organize two panels at the Bergen Exchanges this year, which we are excited to participate in. The first panel will be on “Urban inequality and securitization,” which will engage with questions relating to the relationship between urban inequalities and new technologies of surveillance, such as algorithmic governance, drone technology or facial recognition. During the pandemic, we have seen the introduction of intensified surveillance practices (cameras, cell phones, heat detectors) —such as curfew and urban zoning—that one would in a pre-pandemic era have deemed draconian or, at least, deeply problematic from a human rights or political perspective, and this panel will discuss these in relation to urban inequalities.

The second panel will be on Knowledge inequalities and decolonizing academia and will discuss the calls to fundamentally re-think knowledge regimes, epistemic traditions and the nature of academic practice, including the institution of the university. What can the nature of trans-continental research and academic partnerships be in light of such perspectives? What would a decolonization of the academy — or academic practice — involve?”