Still caring about last winter's snow?

With all the rain pouring down this autumn, some may already look forward to an equally snow-rich winter as last year's in Western Norway. While the seasonal forecasts have not yet reached a consensus, at least by now some Bjerknes scientists know more about last year's snow.

Main content

In April of 2018, just before the Easter vacation, I, as leader of the SNOWPACE project, invited Bjerknes scientists for a pilot citizen science project. How useful are samples of fresh snow taken by average skiers enjoying peak snow with sunshine at their "hytte" for a top-notch research project?

The team got six participants that picked up their snow sampling kit: a spoon, several bags, three glass tubes with a unique sample ID on it, and a sampling sheet. Out of the six participants, five finally did take a sample, and delivered up to three glass tubes with melted snow from the Norwegian "påskefjellet" (literally meaning Easter mountain, this is a well-known Norwegian concept). With such a citizen science project, not everything goes as expected. Some sample tubes dropped and broke on the way home. Some tubes leaked, and some took several weeks to finally return to the lab. The overall success rate was still impressive, with 16 returned samples out of 23 that were handed out to participants - a success rate of 70 percent!

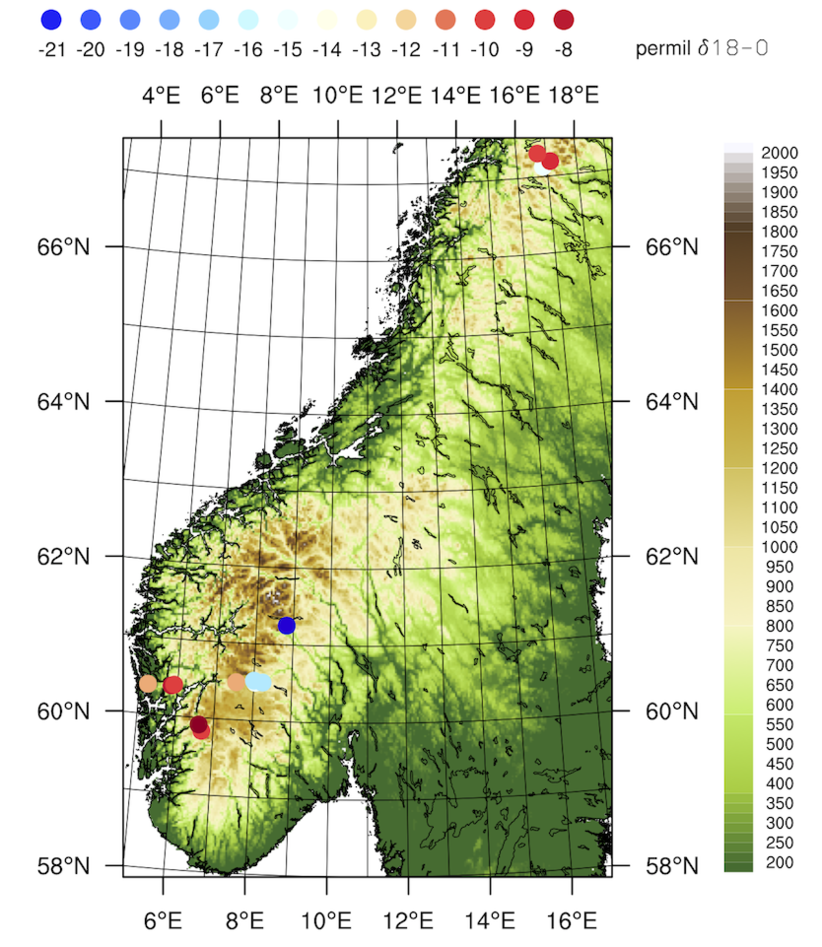

And the coverage was overall quite impressive as well. Samples were taken over a period from 23 March to 01 April 2018, between the region of Finse and northern Sweden, and with an elevation range of between 150 m to 1270 m above sea level (Fig. 1). While the scientists had hoped for fresh snow, the Easter vacation week was mostly windstill and sunny. In any case, there was surely enough snow around this year to at least take samples of the older snow pack.

Back in Bergen, SNOWPACE scientists analysed the samples at FARLAB by injecting one millionth of a litre of the sample water into a heated tube, where the water first evaporated, and was then guided further through into an analyser where a laser tuned to the absorption wavelength of different isotopes of water waited for the making its measurement.

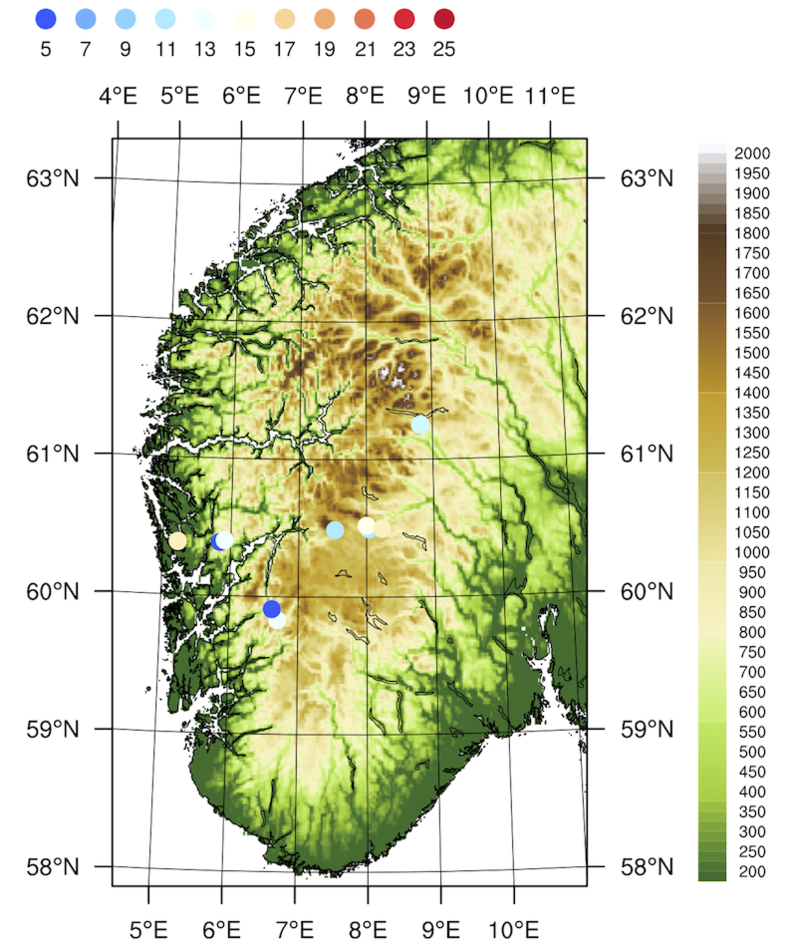

Given the wide spatial coverage of the samples, also measurements showed a substantial variation. The general pattern is that these heavy isotopes become more rare the further air moves inland (Fig. 1). This is what the scientists expected, since due to their lower vapour pressure heavy isotopes condense and rain out first. Compared to ocean water, the samples contained between 0.73 to 2.15 percent less of the heavy isotope 18O. Another parameter, the Deuterium excess, indicated that evaporation conditions were dominated by a situation with a cold atmosphere over a relatively warm ocean (Fig. 2). One sample showed a large outlier that could be traced to a leaky sample tube.

Overall, it is impressive what can be achieved with a targeted citizen science project. Based on minimal preparations and organisation, and at minimal cost, a wide spatial coverage could be achieved, with 70 percent success rate, good documentation, and timely return of samples. Next Easter, the citizen science project will be expanded to include a larger audience, adding more UiB employees and the University of Oslo. The project scientists are already curious what next year's snow will have to tell.

This is also publised at the web-pages of The Bjerknes Centre for climate research.