Venice California, Gentrification in a Neo-Bohemian Beach Town: Structural Violence, Power structures, and Ideological Justification for Injustice, Exclusion, and Dispossession

Main content

Master's thesis submitted at Department of Social Anthropology, spring 2021.

By: Michelle Marie Saliba Fredriksen

Supervisor: Associate Professor Iselin Åsedotter Strønen

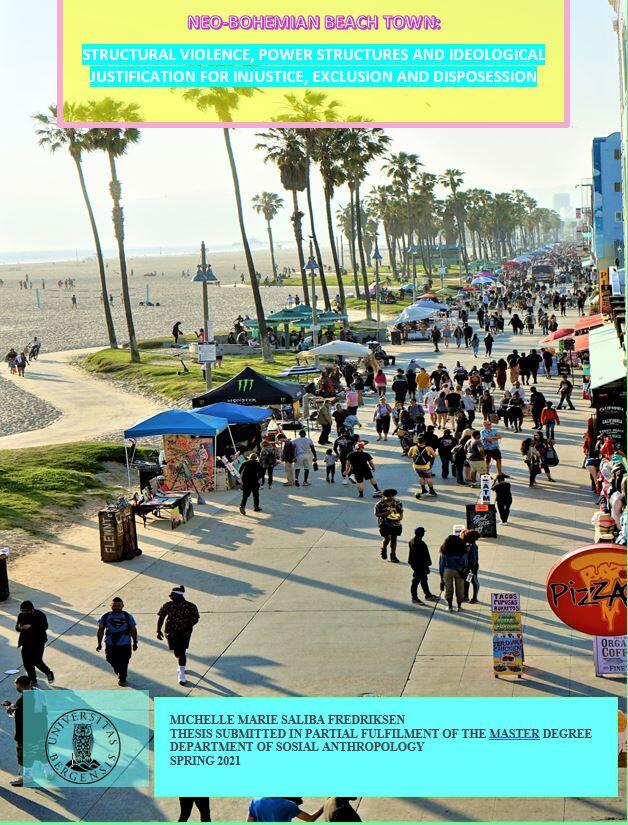

Venice California was envisioned and founded by the wealthy tobacco mogul, Abbot Kinney. Kinney constructed the whole infrastructure of a city in a decade. From its opening in 1905 until 1925, Venice was a thrill seekers paradise, with an intricate canal system, and several amusement piers. Venice, California is the second biggest tourist attraction in California after Disneyland, with 16 million annual visitors (L.A.M.C. 2020:2). Venice is in popular imagination seen as a creative hip, cool, place for unrestrained lifestyle, which is reproduced through popular culture, commodified and materialized through fashion, movies, music videos. Venice is famous for being the home to the Beatniks in the 1950s, Hippies (Deener 2007) as well as being a place for freaks and the radical left (Mcbride 2008) in the 1960s and 70s. Venice has been rapidly gentrified since the 1980s. The artistic “vibe” and the sociability of social spaces is one of the major motives for gentrifiers to move to Venice. Although gentrifiers often frame their aspirations to live in Venice through “ideological consumption patterns” (Zukin et al. 2009) such as “preserving the “authenticity” (Zukin 2011) of Venice trough “social preservation” (BrownSaracino 2013), gentrifiers ultimately end up changing the “authenticity” they seek to preserve, by establishing businesses that fit the tastes of the middle and upper class. Before the process of gentrification occurred in the 1980s, Venice had suffered from neglect and was artificially deprived because of segregation laws, restrictive covenants, and redlining that deprived the ethnically mixed working class neighborhood of upward mobility. A newfound interest in Venice occurred in the 1950s when the powerful elite lobbied urban renewal strategies, in which they legally sought to dispossess and evict many of the working-class people. While previous efforts of exclusion was framed in explicitly racist policies, exclusion caused by gentrification is formulated in line with “neoliberal reason” (Brown 2015) which claims to have no raceor class-exclusion on the agenda. However, with the process of gentrification, Venice is becoming more and more homogenous, with an over-representation of white middle and upper-class, professionals. Moreover, with gentrification also comes exclusionary practices in public spaces. Particularly the unhoused vendors on Venice Beach Boardwalk are a target for anti-homeless laws formulated by the Municipality of Los Angeles. The exclusion of unhoused persons is justified ideologically through the distinction of the “undeserving poor” (Katz 2013), where people who live on the boardwalk are prescribed a certain stigma which is seen as an objective truth. The stigma that unhoused persons are prescribed is reproduced as a social reality which forms discussions in formal political forums like the Venice Neighborhood Council. Although the current technique of differentiation is formulated in line with neoliberal reason through the process of gentrification, I argue that these are power structures based on systems of differentiation that dates back to the colonial era.