Study Reveals Early Microbial Feasting

Tuesday 30 April 2013

Main content

The first ever snapshot of primitive organisms eating each other has been found in ancient fossils examined by David Wacey and Nicola McLoughlin from the Centre for Geobiology and Department of Earth Science.

The fossils, preserved in 1,900 million-year-old Gunflint chert from Lake Superior, Canada, capture ancient microbes in the act of feasting on a cyanobacterium-like fossil called Gunflintia – with the perforated sheaths of Gunflintia being the discarded leftovers of this early meal.

“Instead of carbon dioxide these microbes were using previously formed organic matter and breaking it down, much as humans do after dinner, in a manner of feeding called ‘heterotrophy’,” lead author Dr Wacey said.

The research, published today in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, provides both physical and chemical clues to primitive heterotrophy. Wacey and McLoughlin, together with colleagues from Oxford University, the University of Western Australia, and the University of New South Wales, analysed the microscopic fossils using a battery of new techniques and found that Gunflintia was more perforated after death than other kinds, consistent with them having been eaten by bacteria.

In some places many of the tiny fossils had been partially or entirely replaced with iron sulfide (‘fool’s gold’) a waste product of heterotrophic sulfate-reducing bacteria that is also a highly visible marker. Crucially, the sulfur atoms in this fossil pyrite carry a distinctive isotope signature that is diagnostic of the heterotrophic bacteria. The team also found that these Gunflintia fossils carried clusters of even smaller spherical and rod-shaped bacteria that were seemingly in the process of consuming their hosts. Similar processes of heterotrophic consumption are still happening today and can often be detected by the smells they emit, such as the rotten egg smell of hydrogen sulphide.

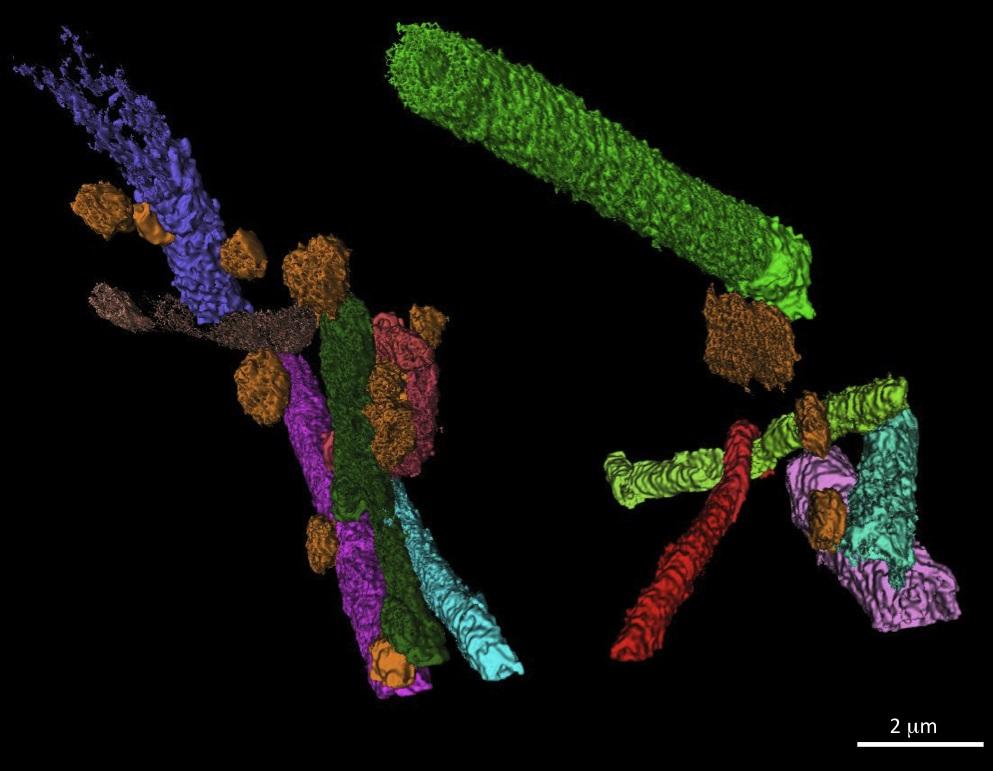

Dr. Wacey adds that until now it has proved difficult to find direct fossil evidence for this heterotrophic mode of feeding. Whilst the Gunflint fossils are much younger than some of the earliest evidence for life itself, these findings confirm that heterotrophic bacteria were indeed flourishing by 1,900 million years ago. And that they were also highly particular about what they chose to eat, appearing to prefer to snack on Gunflintia as a ‘tasty morsel’ in preference to another bacterium (Huroniospora).” Essential to this study was the development of microscopic reconstruction techniques that were used to image the microfossils in three dimensions within the rock. Previously, the authors have illustrated the power of this technique to investigate a number of very ancient microfossils (Wacey et al. 2012 Precambrian Research).

Read the paper at PNAS online here

The study was carried out with the aid of funding from the University of Bergen, Bergens Forskningsstiftelse, and the Norwegian Research Council.