Mare Nullius: Professor Edvard Hviding awarded Toppforsk grant

Social anthropologist Edvard Hviding is one of three University of Bergen researchers to receive five years of major funding from the prestigious Toppforsk programme, awarded by the Research Council of Norway, for his project Mare Nullius.

Main content

The project Mare Nullius? Sea-Level Rise and Maritime Sovereignties in the Pacific – An Expanded Anthropology of Climate Change has been developed over many years by Professor Edvard Hviding of the Department of Social Anthropology at the University of Bergen (UiB).

Between 2012 and 2016 Hviding coordinated the international collaborative project ECOPAS, funded by the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP7). In the years 2008-12 he directed the Pacific Alternatives project, funded by the Research Council of Norway. Both projects involved partners in Europe, the Pacific Islands region and North America, and gave a prominent international role to the university’s research group Bergen Pacific Studies, that Hviding leads.

A feeling of personal indignation

The Mare Nullius project poses some uncomfortable questions about the condition of our globe: What happens when entire nations stand to disappear from climate change and rising sea levels, a scenario faced by several low-lying Pacific Island countries? What status is accorded to those who have to leave islands that are no longer inhabitable? And, what is the fate of the 200-mile exclusive economic zones (EEZs) of island states when the land upon which maritime boundaries are based is inundated by a rising sea?

“For me, Mare Nullius is the culmination of 32 years of research engagement in and with the Pacific Islands. The project’s background is one of personal indignation on behalf of the people of the Pacific, who have cared for me so generously. They contribute the least to global warming, yet are set to suffer the most from its effects. Through my fieldwork in the Solomon Islands and encounters and conversations over three decades with people from most of the Pacific, I have been deeply engaged in the fight by the island nations against rising sea levels, intensified extreme weather and other effects of global warming,” Edvard Hviding explains, adding:

“The ECOPAS project was anchored in our mantra “Restoring the Human to Climate Change”, through which we set a spotlight on the human costs of climate change, on many levels.”

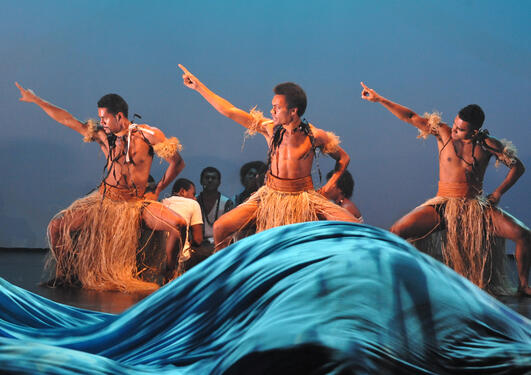

Among many of ECOPAS successes is the University of the South Pacific’s climate change stage drama “Moana: the Rising of the Sea”, which was performed at the Bergen International Festival and on a subsequent European Tour. The performance told the islanders’ own stories of how climate change takes its toll on their lives.

On 8-9 February 2018, Hviding has a central role when the conference Knowledge for Our Common Future: Norwegian Universities and the Sustainable Development Goals takes place at UiB. He suggests that the challenges to be explored in Mare Nullius finds a place within several SDGs.

Strategic research areas, sustainability and science diplomacy

The anthropologist also notes that the project takes centre stage in relation to UiB’s strategy for 2016-22 – Ocean, Life, Society.

“Mare Nullius embraces all UiB’s three strategic research areas: global challenges, climate research and marine research. We are addressing something as fundamental as the global political fate of the ocean in the era of climate change,” Hviding notes.

He is also one of the main contributors to UiB’s current drive to engage in an active advisory capacity towards government and international organisations; an activity also referred to as science diplomacy. The Mare Nullius project includes anthropological fieldwork in the diplomacy of the United Nations and at climate change summits; a strategy developed by Hviding and colleagues in the ECOPAS project.

“My vision is to contribute to the building of new anthropological method and theory, for fieldwork-based studies of international political practice,” Hviding explains, continuing:

“I have developed this project in dialogue not only with a network of research partners in many parts of the world, but also with the United Nations missions of the Pacific island nations. It is the UN ambassadors of the Pacific who handle many of the daily challenges to wider global recognition of the consequences of climate change for their countries. But in fact they engage in this fight on behalf of us all. My ambition is for Mare Nullius to contribute to broader knowledge of how the Pacific island nations engage as state actors in global legal and diplomatic systems, and to providing the climate change challenges with a clearly humanist dimension grounded in Pacific islanders’ own perspectives, hopes and ambitions,” Hviding says.

A highly interdisciplinary project

Mare Nullius builds on interdisciplinary approaches developed in the ECOPAS project, where Hviding collaborated with climate scientists at UiB’s Bjerknes Centre for Climate Research and at the University of the South Pacific. Climate science has a central place in the new project too, but will be integrated with legal studies, political science and maritime global history.

“The project’s basic agenda connects climate science and law to anthropology as the central, integrative discipline. I aim to develop what I see as a true interdisciplinarity, which also includes the indigenous knowledges of Pacific islanders,” Hviding explains.

One of the project objectives is to document the actual building of interdisciplinarity. Mare Nullius will offer PhD and postdoctoral positions in the participating disciplines, and will interact with an international group of prominent scholars. The new joint Chair of Oceans and Climate Change being launched by the UiB and the University of the South Pacific as a follow-up of the United Nations Ocean Conference 2017 also takes part in the project.

“For the project’s PhD and postdoctoral positions we aim for shared supervision across disciplines, as well as significant research time in the Pacific, in the UN system and in other forums where island nations fight for their sovereign territories,” Hviding notes.

Maritime law and climate science are central to the project

Professor Ernst Nordtveit of UiB’s Faculty of Law is one of Hviding’s internal institutional partners in the project.

“The most central legal question is what happens with the EEZs of the island states and the boundaries of their continental shelves when islands become uninhabitable and ultimately inundated by the ocean. Will they be able to retain their exclusive rights to the vast tuna resources which provide them with today’s financial foundation, or will the EEZs turn into open ocean free to unlimited fishing,” Nordtveit asks.

“Many other questions will arise concerning what gives legal refugee status, which cultural and social rights are retained when entire national populations have to relocate, and so forth. This also raises fundamental questions as to which legal principles will apply in the aftermath of major physical transformations that actually change the very premises for those global legal regulations that we have established,” Nordtveit notes.

Professor Noel Keenlyside from the Bjerknes Centre and the Geophysical Institute at UiB will also have a crucial role in the project. He is a leading expert on climate cycles and the effects of global warming on the Pacific Ocean.

“I am really excited to be part of Mare Nullius. While it is clear that climate change will lead to the disappearance of many low-lying atolls in the South Pacific, less clear are the various ramifications for exclusive economic zones. To help address this issue I will be providing information on the timing and extent of the changes in island landscape. I am really looking forward to being part of an interdisciplinary team to address this important societal challenge,” Keenlyside says.

The Pacific as a global challenge

“The current situation is one that is unknown in documented world history: entire states stand to lose major parts or all of their sovereign territory from sea level rise. When coasts and low-lying islands disappear in a rising sea, the very boundaries of 200-mile zones become unstable, which underlines the challenges facing the global community,” says Edvard Hviding, adding:

“By combining climate science models of sea level rise and erosion of land, legal scenarios of maritime law and state sovereignty, and understandings from anthropology, history and political science of the experiences of Pacific islanders and of diplomatic efforts on all levels, we will create new insights across many levels of scale, from Pacific beaches to global climate change monitoring, international legal fora and the geopolitical stakes of the UN system.”

The anthropologist sees the Mare Nullius project as a component of the UiB’s strategy for supporting the UN Sustainable Development Goals. In this, he sees synergies also with the new Ocean Sustainability Centre established by UiB in January 2018.