Microaggression in Arabic

The first journal for Arabic speakers in Norway, DER, includes in its latest issue a translated version of UiB researcher Randi Gressgård’s article about microaggression: Banging one’s head against the wall.

Main content

The first issue of DER was launched last year by editor Osama Shaheen. DER means “house” in Arabic, and Shaheen explains in this interview with Bergen Chamber of Commerce and Industry that they wanted a title that made sense in both Norwegian and Arabic.

A platform for Arabic speakers

We started the journal in response to the growing need for a platform that addresses issues relevant to Arabic-speaking people in Norway.

"Refugees and migrants are routinely discussed in the media, and the discourse doesn’t necessarily tell the truth about these people," says Shaheen.

"The discourse is shaped by society and vice versa. That’s why it’s important for a group of more than 140 000 people in Norway to have platforms like these."

Microaggression affects Arabic-speaking students

Shaheen discovered Gressgård’s 2014 article as a student taking classes in the one-year programme Gender, sexuality and diversity at the Centre for Women’s and Gender Research (SKOK); on the reading list of the course KVIK102 – Equality and diversity.

Å stange hodet i veggen: Mikroaggresjon i akademia (in English: Banging one’s head against the wall: Microaggression in academia) addresses how microaggressions work in relations both between employees and between employees and students and shows how academic norms and ideals have marginalizing effects on women and minority groups within academia.

According to Shaheen, the article helped him understand microaggression better, and since this is a problem that affects many Arabic-speaking students, Shaheen wanted to translate a shorter version of the article for the new issue of DER.

"Through many conversations with Arabic-speaking students born outside of Norway, I have learned how isolated they’ve felt at the university; both in group work, lunch breaks and extracurricular activities. It’s been particularly difficult for students who recently arrived in Norway."

A less than inclusive environment

Shaheen says that this might partly be due to language barriers and lack of knowledge about social codes. Still, he has heard many stories about a less than inclusive environment in academia.

"It’s sad since some of these students have dreamt about and tried to get into university for a long time. They are very motivated to be part of the university environment, but they are not heard or seen."

According to Shaheen, almost everyone he talked with told him they didn’t feel included in the university environment.

"The university just becomes a place where they listen to the lecture, and then return home quickly afterwards. I believe that this is very important to discuss, and Gressgård’s article about microaggression succinctly describes these kinds of experiences."

No word for microaggression in Arabic

Shaheen explains that Arabic-speaking students lack the language to put their experiences of microaggression into words. Part of the reason for this is the Arabic language.

"Even if Arabic is a rich language, it doesn’t have a term for microaggression. The 'laziness' of the Arabic language prevents it from finding translations of a number of terms, which are simply written in Arabic letters as pronounced."

Shaheen explains that by laziness he means an absence of a discussion, which makes it hard to describe the mechanisms of racism.

Language is a reflection of society, and if society doesn’t change and fight against these mechanisms, the language isn’t activated to reflect this tendency. That’s why we in DER believe that Gressgård’s article can help students to learn about microaggression and find words to describe it.

Still hard to problematize institutional racism

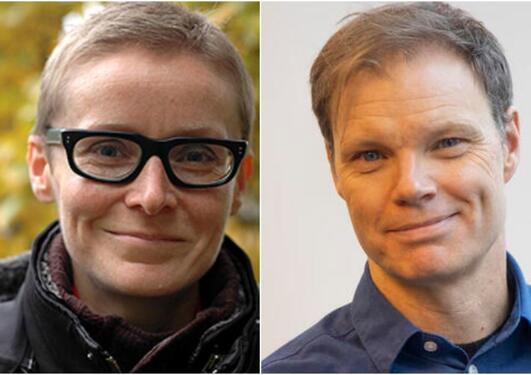

In the article, Gressgård concludes that a focus on microaggression could work to problematize the institutional framework in a more fundamental way than what existing regulations on antidiscrimination allow for.

With the growing attention on institutional racism in academia and society at large since the article was first published, there is more awareness around informal, structural mechanisms of oppression, according to Gressgård. However, she believes that it is still hard to problematize institutional racism and inequality based on gender and sexuality.

"Out of habit, most people see discrimination as an individual and intentional inequity problem, calling for individual sanctions or solutions," says Gressgård.

She also highlights the fact that terms like microaggression, intersectionality and critical race theory have become more politicized and opportunistically misused in the so-called culture war, as outlined in a recent op-ed by Gressgård and her UiB colleague, Asbjørn Grønstad, entitled Væpnet til tennene med ytringsfrihet (in English: Armed to the teeth with freedom of speech).

"This makes it all the more important to problematize power structures that are invisible to most people but exhausting and damaging for those who experience them on a daily basis. For this reason, it’s timely that the journal DER now wants to draw attention to microaggressions."

On 4 May, there will be a release party for the new issue of DER at Litteraturhuset i Bergen.

"We have invited four amazing guests," says Shaheen: "Labour party politician and Oslo’s deputy mayor Kamzy Gunaratnam, Line Khateeb and Rana Issa from the board of the Arabic culture organization Masahat, and Wafa Moustafa, a Berlin-based Syrian activist and journalist."

"We also look forward to meeting the audience if the corona measures allow for it."